In this week’s post, I explain how tax efficiency is important for compounding.

In our previous series on account and security types, we discussed several different types of investment accounts that have special tax treatment – traditional IRA, Roth IRA, 529 plan, health savings account (HSA). However, in discussing these different account types, we did not fully discuss why being tax efficient is so important. Tax efficiency maximizes the power of compound interest.

What is tax efficiency?

Being “tax efficient” means minimizing the impact of taxes over the investor’s entire lifetime. Of course, taxes are complicated and always changing, so a number of assumptions have to be made. For example, even a seemingly simple decision of choosing to contribute to a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA requires many assumptions to be made about the investor’s future income and future tax rates. It is also important to note that the timing of tax payments is important in minimizing the impact of taxes over the long term – an ideal scenario might result in a higher dollar amount of payments being made, just with the payments pushed far into the future. Regardless, just remember that the goal is to minimize the impact of taxes over the long-term and maximize the value of the investor's after-tax portfolio.

This post will emphasize the importance of being tax efficient, however, we will not be discussing how to be the most efficient. We hope to cover different strategies in future posts.

Tax efficiency is important for compounding

As a reminder, compound interest is how, when reinvested, interest on any investment return builds on itself – interest is earned on interest.

As mentioned in previous posts, when running a compound interest calculation, there are several different inputs: the rate of return, starting amount, contribution amount, frequency of compounding, and number of years invested. The impact of taxes does not necessarily fit perfectly into one of these inputs. Taxes could be seen as negatively impacting the rate of return or being a separate, negative contribution amount. Regardless, paying more in taxes leaves less to be compounded.

Example comparing compounding in a tax-free (Roth) account and a taxable investment account

Let’s look at an example. An investor contributes to a Roth IRA and another investor, who does not like the additional rules of the Roth, contributes to a taxable investment account.

As we discussed in our post about Roth IRAs, a Roth IRA is funded with after-tax money. The funds grow tax-free and can be withdrawn tax-free in retirement.

A taxable account is funded with after-tax money. Dividends are taxed, often times at special tax rates. Realized capital gains are also taxed. Realizing capital gains can be deferred by not selling any holdings. However, typically, holdings are eventually sold. One way to quantify buying and selling in a portfolio or fund, is to look at the portfolio or fund’s “turnover,” which indicates how much buying and selling is going on. The taxation of capital gains and dividends can get a little complicated, and will likely be the subject of a future post or series of posts. However, at this point, it is important to note that they can receive special tax treatment.

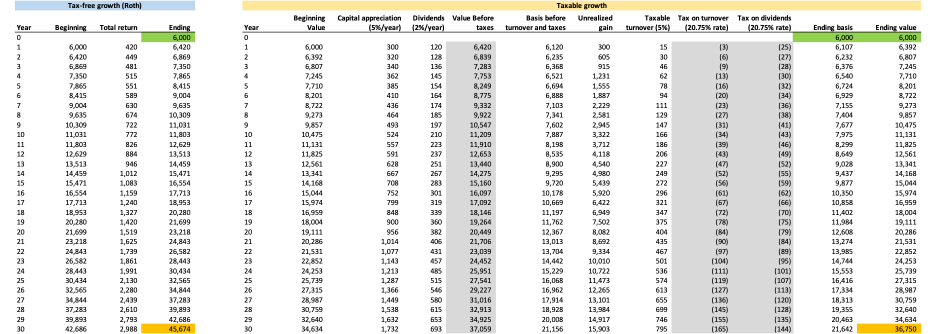

Both investors contribute $6,000 to their respective accounts. Both accounts earn 7% a year. How the return is split between capital gains and dividends is important when analyzing the taxable account, because of the different tax treatment of dividends and capital gains. Let’s assume the 7% total return comes from 5% capital gains and 2% dividends. Both accounts are invested for 30 years. The turnover of the taxable account is 5% a year, which is very low as compared to many portfolios. The owner of the taxable account pays 15% federal and 5.75% state for a total rate of 20.75% for both long-term capital gains and qualified dividends. At the end of 30 years, the tax-free (Roth) account will grow to $45,674. The taxable account will grow to $36,750, which is just over 80% of the tax-free account. Also, the taxable account will have a tax basis of $21,642, meaning that liquidating the account may have further tax consequences, resulting in an even smaller ending value.

Here is a chart, showing the two accounts:

This example clearly shows the importance of being tax efficient and how being inefficient can limit the power of compounding.

Here is a graph showing the two scenarios:

There are a number of assumptions that went into this comparison, particularly about how to handle turnover in the taxable account and the tax basis of the account. It gets a little nuanced and I will not describe the process here, but feel free to reach out if you would like to learn more.

Here is the spreadsheet with the calculations (may be hard to read on a phone):

This will be the last post in our series on compound interest

I hope you have enjoyed this brief series on compound interest. We have covered and emphasized several different aspects of compound interest:

Tax Efficiency Is Important For Compounding

Compound interest is important and should be leveraged to help you reach your financial goals!

If you have any comments, questions, or ideas for future posts, please let me know

I hope you found this post helpful and educational. If you have any comments, questions, or ideas for future posts, please let me know. You can reach me directly via email at crawford@ulmerfinancial.com.

Comments